The Roald Dahl edits are not 'woke'. It's just business as usual

Let's not get sucked into a culture war here.

It’s become something of a cliche to say that western pop culture has condemned itself to an endless retread, remake and reboot of brands and motifs from the late twentieth century. It’s not because people suddenly ran out of ideas. With capital’s profit margins ever more under pressure, cultural investment favours the safety of name recognition over innovation.

Which brings us to the news that new editions of Roald Dahl’s children’s stories are being released, with a whole lot of editing to remove words and sentences deemed out of step with modern sensibilities. I first heard about this story through a very typical culture wars frame, one in which the publishers were lambasted as ‘woke’ censors, making the changes to a beloved author on behalf of permanently offended ‘snowflakes’. The word woke has become a sort of culture war lodestar; a word that originated in the social and political activists of the marginalised African-American communities, has now been appropriated by right wingers to rally their band of useful idiots against anything and everything that may make even the smallest positive change to society.

Not that I think these edits are a positive, but more on that later. There’s also, somewhat predictably a sort of kneejerk response among some on the left wing, to respond in-kind to these kind of framings. If the right labels something as ‘woke’ then it’s likely that thing is a good thing, right? Sometimes this is a useful strategy, but other times it can put the left in the silly position of defending very transparent and cynical attempts by corporations to wash their commodities with a sheen of social justice.

I guess it would be great if we could just ignore all this, but ‘culture wars’ can play into more serious politics too. It’s almost as if those in power are cynically using culture as a way to divide the working class, isn’t it?

So then, what of the Dahl editing? In 2021, Netflix acquired the rights to Dahl’s children’s stories and have employed Inclusive Minds, a collective whose aim is to make children’s literature more inclusive and accessible, to consult on the corpus.

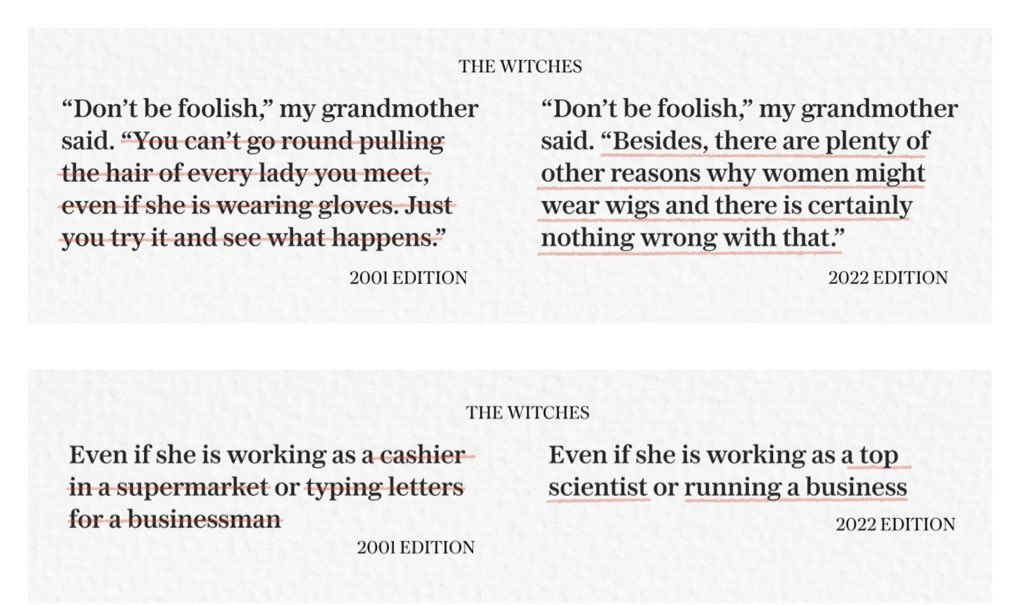

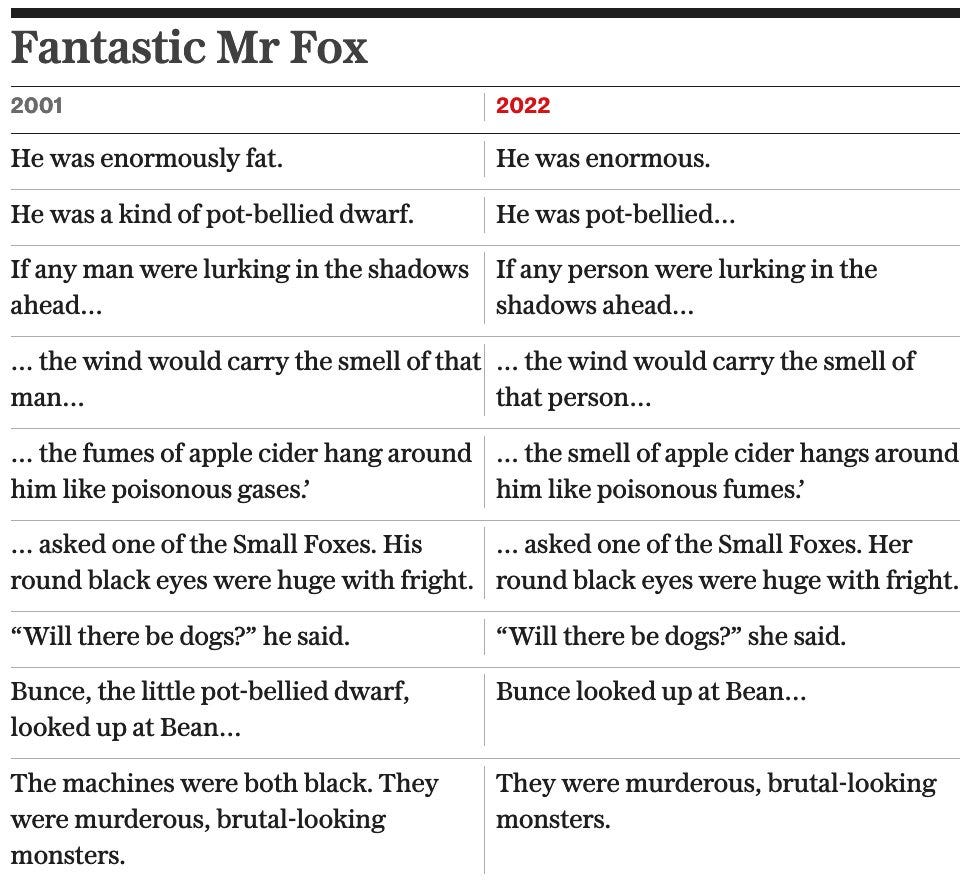

Dahl’s prose and ideas are certainly known for their spikiness and I’m sure that was part of the reason why I loved them as a 10 year old kid. There’s also a fair bit of meanness and downright nastiness too, and indeed this isn’t even the first time that his work has been edited. In his lifetime, he (reluctantly) changed the initially racist description of the Oompa Loompas in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory who, in the 1964 edition, were introduced as being from ‘the very deepest and darkest part of the African jungle where no white man had ever been before’ and ‘near starvation, living on vile caterpillars, so Wonka smuggled them to England for their own good’. It was only when the US movie was announced that edits were made to make the Oompa Loompas more fantastical characters than the offensive stereotypes that Dahl’s colonial mindset had conjured.

Probably the best way to gauge whether you think these edits are justifiable, is to imagine yourself reading the story to a child and whether you would omit/edit any of the text yourself, or perhaps pause and explain to the child that Dahl’s writing needed to be seen in the proper historical context of it’s time (probably in a much simpler language). There’s certainly a few here that you could say are justified; “typing letters for a businessman” surely must have been felt dated at the time of its original publication. Similarly, through 21st century eyes, gendered insults like ‘hag’ or the use of “dwarf” in a negative sense have a bite to them and the logic of their omission makes sense. Changing the little foxes in Fantastic Mr Fox from male to female is a harmless change that does little to alter the narrative.

Other changes are head-scratchers, why change “fumes” to “smells” or remove the word ‘fearful’ from ‘fearful ugliness’? There’s a certain whiff here of not just social justice, but corporate-induced blandness, the type that took the word philosopher out of the original Harry Potter US edition, because publishers were worried kids wouldn’t understand it.

These reviews were not to make a cultural statement in service of social justice, but rather for money for the estate and Netflix. The company, instead of investing in contemporary authors who may have something new to say, wanted to have their cake and eat it, to maintain a grip on a known brand intellectual property while simulataneously making it palatable for the modern market.

This wouldn’t be a problem if we didn’t live in a society where the works of long dead authors were allowed to become jealously guarded ‘intellectual property’ of estates. I don’t care if someone makes an edit to Charlie and the Chocolate factory, I care that a only a corporation is allowed to and is given the legal right to aggressively shut down everyone else from doing the same.

Imagine instead a world where the works of Dahl were public commons, available to all to freely edit to their hearts content (and yes, remove some of the sexism and meanspiritedness if they wanted to). Wouldn’t that be a much better way that Dahl could be honoured as a writer? Humanity’s best stories, the ones passed down from generation to generation, have been edited and retold countless times. That’s what makes them legends.

Theory Time

Marxist economics showed us that the products of labour owe their existence to those who laboured to make them rather than those who had the capital to legally own them. Marxist-Feminism built on this and introduced social reproduction, a new layer of de-fetishisation to our understanding of social products. In short, behind every wage labourer was a whole lifeworld of support in various forms of tangible and intangible labour, labour that was both unpaid and unrecognised.

The same can be said for intellectual property. Not even Roald Dahl himself can claim that the creation of his oeuvre was the output of his energies alone. He was not some Olympian god sitting in the clouds cascading down stories to another plane of existence. In his life, whether he acknowledged it or not, he was supported by his family, who gave him direct material and emotional gifts, as well as friends, teachers, workers and professionals, all of whom helped to build the world that nurtured him from cradle to grave. Individual brilliance, which Dahl certainly had, along with being a prick, can only exist in a nest of other’s making.

So, let’s criticize the Netflix Dahl edits for what they are, bland corporate streamlining, but let’s not act like texts are holy either.

Let a thousand edits bloom.