The Blind Earthworm in the Labyrinth (Review)

Pre-internet Bangkok appears like a dream in this Thai novel

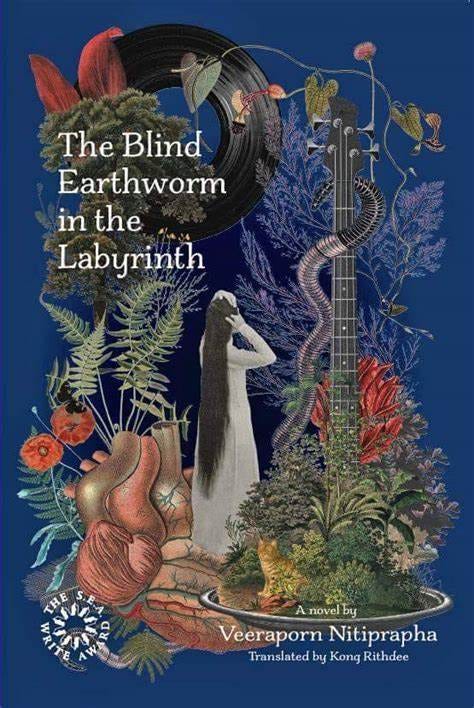

The Blind Earthworm in the Labyrinth (2019) River Books.

There’s a short scene in the Blind Earthworm in the Labyrinth where two characters fall briefly in love listening to Brahms in a Bangkok CD shop. Cursed as most characters in this book are, the boy leaves the country and returns twenty years later hoping to find our heroine again, only to find that CD stores no longer exist, ‘condemned as they were to the graves by data migration’. I felt somewhat similar on a recent trip to Bangkok, as I realised that most of the old bookshops had disappeared.

I first went to Bangkok as a backpacker well over a decade ago. The scene was set by Alex Garland’s novel the Beach, which was followed by the movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio, a tale of backpackers turning into Lord of the Flies. In the book, the hero first arrives in Bangkok’s Khao San Road, the headquarters for those with dreadlocks and dreams (Ok I had the latter but never the former).

Amidst the hawkers selling pad Thai, fried scorpions, and elephant pattern fisherman pants, what I always loved about Khao San road were the second hand book shops. They were a fascinating glimpse into the psyche into the collective imagination of the backpacker and the sort of people that ended up in Thailand. The likes of Kerouac, Garcia-Marquez, Kundera, Murakami, Roy and Eco, were the sort of fiction a fresh undergraduate would hope to be caught reading while they downed their coffee and banana pancakes. For those seeking real world insight into the Asian world, the jade green cover of Jung Chang’s Wild Swans was an omnipresent sight on the backpacker trail. Less well renowned but still cracking page turners were the sordid memoirs of Thai bargirls and western drug smugglers who ended up in Thai prisons. Every second hand backpacker bookshop would also boast a small cache of the estoreric: books on the new world order, on aliens and shamens and the men behind the curtain, written by authors you’d never heard of and publishers that probably never existed in the real world. It was a gentler time, when conspiracy theories were a fun way to spend an afternoon chatting nonsense and not the kind of intense and increasingly rightwing-coded discussion they have become.

So, this past month, I was dismayed to find all the bookshops had been replaced by weed dispensaries, now that it has been decriminalised. Call me old fashioned but for me, the authentic Thai marijuana experience wasn’t smoking something called ‘mad kush’ in a plastic shop with shitty techno music in the background, but having a few cheeky midnight tokes behind the guest house before getting major paranoia attack that the entire Thai constabulary were about to batter the doors down and ship you off to prison, where presumably you would end up writing a memoir that over the course of time would end up on the coffee table of that very guesthouse.

No one reads anymore, instead they are glued to their smartphone and tablets and seek validation, not in the page but in the Instagram engagements and I’m including myself in this. I long for the days where I would spend whole days reading. Is it a new demographic or a new way of life? Have the hippies been replaced or transformed like the invasion of the bodysnatchers? It’s probably bit of both, and if we really want to drill down, the true hippies these days are too busy heroically acting as humanity’s vanguard amidst the threat of climate change.

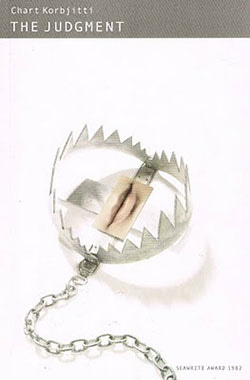

I’m sure the older heads looked on my generation as a bastardization of their purity too. There’s actually a scene in The Blind Earthworm in the Labyrinth, set in the 1990s, where two of the main characters go to Khao San road to source a bottle of Chilean wine and then drink it by a lonely pier on the Chao Phraya. Now that really is a tale of a time gone by. Still, my own present bohemian Bangkok fantasy needed a café and a good book and and I knew just where to go. Passport Books is a lovely little Thai bookshop catering to Thai literary scene and with a little section of Thai novels in translation. It’s the sort of place where staff members write little notes of recommendation on special books, which is what led me ten years ago to pick up The Judgement by Chart Korbjitti. I’m not going to do a review of that book, but in short it’s one of those books that hits you so fucking hard you never forget it. Essentially a story of a man who falls through the cracks, there’s little drama or plot so to speak, just unrelenting sociological grimness and I know that isn’t exactly going to get you running down to the bookshop, but seriously if you read one Thai book, then make it that one.

But this isn’t about that book, it’s about another one. The owner of the bookshop recommended that I get a book by Veeraporn Nitiprapha, an award winning Thai author. One of the review blurbs on the back of the Blind Earthworm said that Nitiprapha is ‘Thailand’s Arundhati Roy’. That was good enough for me. So what’s it about? It’s a tale of 80s and 90s Bangkok centred around two sisters, Chareeya and Chalika who grow up in a semi-rural house on the outskirts of Bangkok. Eventually they are joined by Pran, an orphan whose evolving relationship with Chareeya forms the backbone of the story.

At first, there’s very plot here to speak of. Each chapter feels like a vignette into the lives of the various characters as they grow up through the 80s and 90s, moving back forth between the garden estate and Bangkok. The lives of Charee and Lika are almost disarmingly quaint and the writing appears to focus more on the flora and fauna of the small estate than anything else. She gives formal names to her flowers like ‘Majestic Auntie Saiyut, All Embracing Auntie Huu Kwang, and Miss Pu-Ranhong’. Later she somewhat implausibly ends up with a garden in the centre of Bangkok, whose flowers and scents appear to be part of the charm that brings Pran back into her life.

The writing is superb, flowery and evocative while remaining grounded to the senses. Pran’s life of meaningless sexual conquest is described with wonderful metaphor as ‘awkward, slow and soundless, like two Siamese fighting fish grappling each other in a bottle of glue.’ Nitiprapha is a master of muted melancholy, and this is a book to savour like a deep bouquet.

Alongside fragrances, the characters inhabit a very bespoke lifestyle, one coded as Western-looking middle class. References to The Cure, Frida Kahlo, Mogdiliani, Schumann, Elgar, Brahms, Les Miserables pepper the chapters; perhaps this is Nitiprapha’s cultural autobiography, complete with a playlist and comprehensive list of flowers and plants at the end of the book. Despite the large amount of Western cultural touchstones, this is still very much a book rooted in Thailand, and one of the most memorable pairs of scenes is Chareeya and Pran gazing up at the Buddhist murals at Suthat temple, watching whales, kinnari and Jatayu come to life amidst the paintwork.

The first third may test readers who seek page turning thrills from their novels and the characters who float from one situation to the next, at least in the first half of the book, may at times get a little too cutesy. Yet the dreamy quality is also seductive and as the story evolves, the numerous diversions and kooky side stories begin to weave a beguiling tapestry. From the lovelorn woman who ends up inadvertently starting a shrine that emerges from a rumour of a lovelorn suicide to Charee’s vivid quest to find an underground city, to the maid Nual, who has five children from three fathers and lives in perfect harmony with all of them, to the tales of Uncle Thanit’s quest for the perfect artisan fabric, it all comes together in the end like tributaries to the ocean.m

As the book reaches it climax, the various eddys of the narrative stream begin to grow into fierce, heart-wrenching whirlpools that suck the reader under with the gravity of what it is to be human. That’s all I can really say without spoiling things and I don’t want to because the way that this book crept up on me. Representative of this is how Chalika’s endless appetite for romance novels appears quaint at first, but by the end of the book it has become a cage of her own making, one that means she can only relate to men as an ‘illusory image…put together from a thousand images stored inside her head.’ I can only hope the images from this beautiful novel do not entrap me in a labyrinth too.